Death of a Developer

The theme for this month’s short story was ‘brief encounter,’ and what could be briefer than an anonymous, paid-for sexual encounter? However, if the young lady in question has reached the end of her tether, her father is her pimp, and the ‘client’ not very nice … Well, it could all end in a murder, or possibly two, couldn’t it?

Stop! Just make it stop!

The thoughts screamed through Miriam Roberts’s brain as she lay on the bed, gasping for breath. The client wanted it rough – and hadn’t bothered to ask first. Why do so many men get off on their women not being able to breathe during sex? Or think a dozen bruises gives her the same pleasure as an orgasm? She was battered, bruised, and as fed up as she could possibly be.

She’d not seen him before, which was unusual at the golf club. But he was vouched for by one of her regulars, so she’d accepted the deal at her usual rate. Which was her first mistake. He said he only wanted to talk – and she’d only gone and bloody well believed him! But his ‘talk’ had been all about pumping her: he’d let on that he was a developer and then she’d said something about Dad and the farm and the mortgage. It was like flicking a switch. He'd got the information he wanted, so he might as well take the physical gratification he wanted as well …

Even before Mum died, her life had been a mess. Dad’s accident, six months after becoming a widower, was a little too convenient. And it was a little too easy for him to get his disability benefits. It became her job to bring in the rest of the money; Dad had this contact at the golf club, where they needed a pretty, young girl like her. They hadn’t worried about her age. She learned to play dumb very quickly.

At last, the developer was getting dressed. Lying on the bed, recovering, it took a second or two before she realised. The bastard was walking away without paying! Normally she made sure she got the cash before stripping off, but he’d started in so fast she was terrified he’d rip the clothes off her – and it wasn’t as if she had an unlimited supply of spare blouses or skirts.

She scrambled off the bed and chased after him: ‘Where’s my money?’ she croaked; her throat still sore.

He stopped, turned: ‘If you were any good, I might have paid. But for that performance …’ he left the comment hanging and resumed his stroll towards the stairs which led down to the clubroom. Miriam screamed in frustration. And put her hand to her neck: that hurt. At the head of the stairs, her ex-client stopped, and turned towards her.

‘I say? Miriam? Is that you? Are you alright?’ Sir Roger, at least ninety years old – all gallantry, but completely ignorant of her real role here – called from downstairs. He thought she was just the barmaid who also cleaned the upstairs room.

‘Miriam?’ he called again.

‘Now then, what shall I say?’ Miriam was careful to keep out of the developer’s reach, but she needed her money, or there’d be another beating coming her way once she got home.

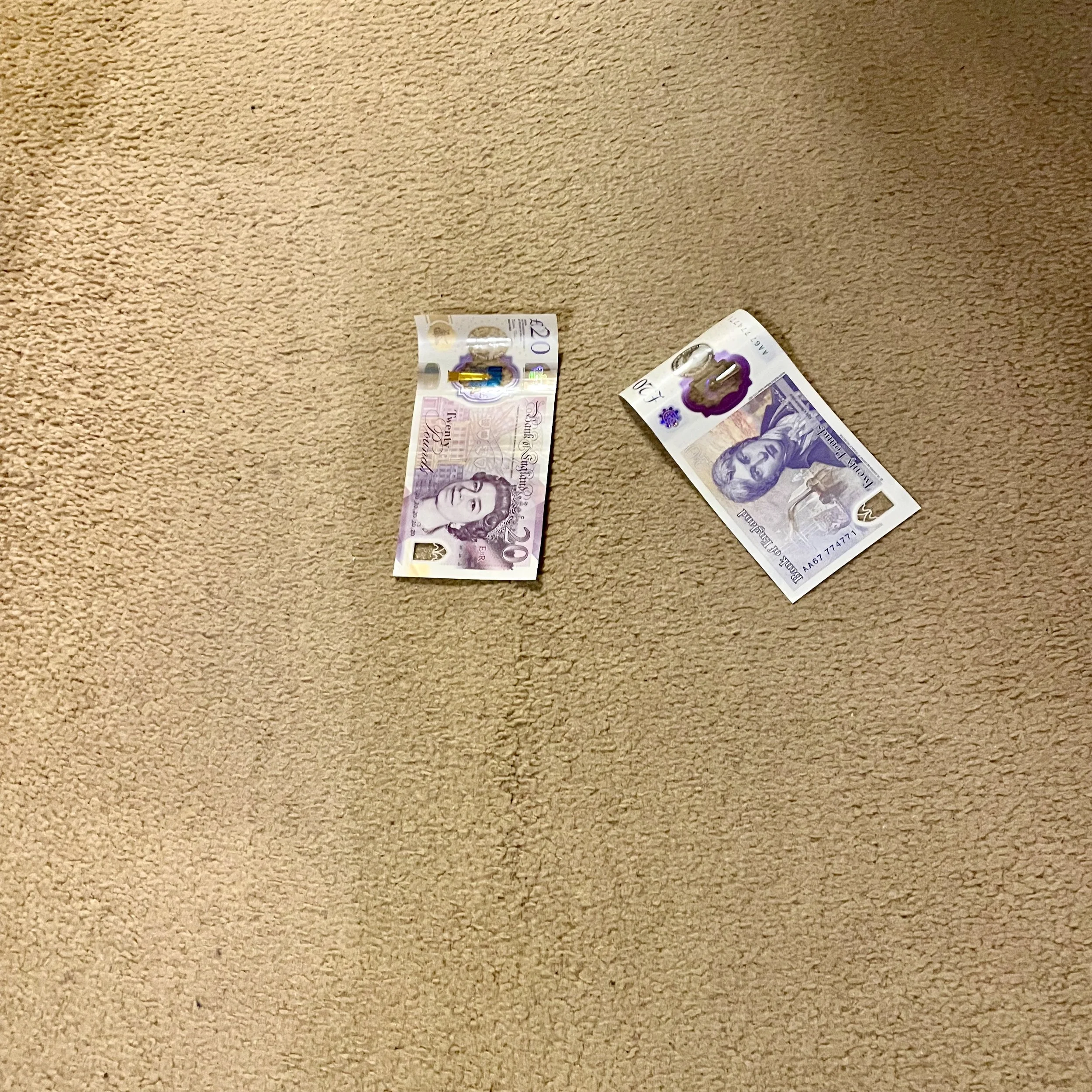

The developer reached into his jacket pocket, pulled out his wallet, and dropped some twenty-pound notes onto the floor. ‘I’ll tell the old fool you dropped an ashtray, shall I?’ he said. Another couple of notes fluttered from his hand: ‘There’s some extra, darlin’ – for the information.’

He’d gone before she could remember what exactly she’d said. She picked up the money, counted it, and went back into the Member’s Bedroom. Not all golf clubs have the facility, but if a member overindulges at the nineteenth hole, this club allows (for a fee) that member to sleep it off rather than risk being caught driving over the limit. (The Member’s Bedroom was created after an embarrassing incident back in the 1990s, when the then chief constable was stopped on his way home.) Of course, the Sir Rogers of the world fail to realise other potential uses for such a bedroom.

As for Miriam’s current predicament, tidying up was easier when they didn’t get in to the bed. She examined the top blanket with care, used baby wipes where necessary – she was not about to face questions over the washing machine going at this time of evening. Despite the outside temperature, she opened the window; only then realising she was still naked. But the room had an ensuite. She used it, cleaned up after herself, got her things together and, caught an image of herself in the full-length mirror.

You can’t live your life scared at every breath, every noise? The breath she drew into her lungs was almost a sob. Then she examined herself: every knock, every scrape, the welts where he’d used his belt on her, all the places where the bruises would show in the morning. Was death really worse than this life? What was her future? Were these to be her days and nights now? Twenty – she was twenty! She couldn’t do this forever.

Ten minutes later, fully dressed, she was at the bar.

‘I’m going home.’

Darren, Dad’s ‘contact’ at the golf club and its bar manager, shrugged: ‘You can’t. There’s another job lined up.’

‘I don’t fucking care! I’m – going – home!’

‘And what will Daddy say?’

‘He can say what he likes!’

‘Alright. Piss off then! But don’t come crying to me tomorrow.’

It was only across the road and up the field. She’d trodden the track every day, seven days a week, since Eddy was old enough to toddle. Eddy was the reason she’d left school without a qualification to her name; what with his arrival coinciding with Mum’s death. Of course, her father’s need for a son meant the pregnancy was much more important than anything Miriam or her mum had to go through. Dad kept Social Services at bay. Not that they tried very hard. Dad would say things like: ‘Look, I’m sure you’re busy. We can’t see you now, but the little chap’s fine. We’re not about to let him play with the farm machinery, are we? Especially after what happened to me.’ Making a joke of it. If the young lady (it was always a young lady) tried to push it, Dad would change tone: ‘Look. Are you saying just because I’m in a wheelchair, I can’t cope? Disabled people shouldn’t have kids? Is that it?’

She would be inside, feeding Eddy, changing Eddy, looking after Eddy. Pretty soon the city-based Education Welfare Officers gave up as well. She was only going to work on the farm, wasn’t she? What would she need qualifications for?

When she tried to complain, Dad made it clear he expected her unquestioning obedience. With Eddy weaned, she could earn some money for him. Dad had mortgaged the farm – again. As a gambler, he had a habit of spending more than they earned. What she’d told the developer was true. However, knowing her dad, he would react violently to the intrusion and blame her for directing him to his door.

At home, having come in by the kitchen, she found her father in the middle of an upturned lounge. Great! So, the developer had turned up, Dad had given him what for, and guess who would have to do the tidying up?

Dad beckoned her over. He snatched her purse out of her hand, grabbed that hand before she could pull it away, and squeezed until she could feel the bones crunching together.

‘You’re hurting!’

The grip slackened a touch: ‘The next time you send a bloody developer up here, thinking he can buy my land for a song, I’ll beat you so hard you won’t sit down for a week!’

‘I won’t be able to work for you then, will I?’ Miriam managed to snatch her hand away while her father examined her haul. It wasn’t worth saying she hadn’t sent him. If her client had asked, she’d have told him not to bother. Dad examined her takings:

‘You’re not doing much work now! You need to do better than this.’

‘Lots of wives in tonight.’ The lie came easy.

‘I’m not selling the farm,’ George Roberts spat, ‘and, if it wasn’t for my accident, we’d be in the bloody poor-house, and you know it. Tidy this place up! Now!’ Her father turned his wheelchair to leave the room, his gloved hands spinning the wheels with expert ease. Miriam watched, impassive.

‘All right, you! Stop standing there and give me a hand!’ He was at the lounge door, expecting it to be opened for him.

At her father’s words, she did as she was told. She had years to be practiced in being wary – his legs might not be able to propel him across the farmyard as they used to, but, from the waist up, he was still a powerful and dangerous adversary.

‘I don’t want any sign he was here. I hurt him more than he hurt me.’ Saying nothing, they went through the usual rigmarole of getting Dad upstairs. Once in his room, she pulled the curtains while her dad peeled off what he called his wheelchair gloves: ‘You can give those a wash – a proper one, mind! – I’ll need them in the morning.’ He flung them in her general direction. ‘And where’s my drink?’

Without a word, Miriam left him and went down to the kitchen. She needed to think about tomorrow’s food as well. The freezer was well stocked: she selected an unlabelled lump of meat. Its shape reminded her of a stone-age axe head; even the string criss-crossing the paper wrapping helped reinforce the image in her brain. All she’d have to do would be to tie a wooden handle to it … Well, Eddy would be amused.

Miriam sighed, and put the joint to one side to thaw. Probably it was venison from one of Dad’s poacher friends. However, she knew better than to ask; she merely had to cook it. She set about Dad’s milky, whisky-enhanced, drink. She was generous with the alcohol, and took the doctored drink to him. She didn’t tell him about the sleeping tablets. Normally, she was the one taking them, but not tonight.

‘Just put it there,’ he was already in bed, pointing at the bedside table, ‘and I want the lounge spotless when I get up.’ He was going to get away with it, and she was the one making the evidence disappear. Somewhere out there, there was a beaten-up developer. She managed a smile and left him to go back downstairs.

First, she checked on Eddy. He would have had the sense to keep out of the way, but she could see he’d cried himself to sleep. He was in the foetal position and his thumb still in his mouth.

I’m getting you out of here, she thought, Dad won’t be keeping Social Services at bay any longer. Not after this!

Three hours later, she stole back upstairs. Her father was asleep and snoring. She crept in and removed the empty mug from the bedside table.

Downstairs, the wood stove was still emitting heat, which, given the fuel she’d used to keep the lounge warm, was unsurprising. However, the log basket had better be full for the next day. She trudged back and forth, rehearsing the plans for tomorrow. She hated not telling Eddy, but telling him would only worry the lad.

Jobs done, she caught a few hours’ sleep. All too soon, it was time to get Eddy ready for school. Had Eddy been older than his seven years, he might have wondered why Dad was sleeping in; but he set off for school much in the same way boys have set off for school since Shakespeare’s day.

He arrived at school breathless, panting, wild-eyed. Only his determined insistence not to retract his ‘ridiculous, stupid story,’ persuaded old Miss Tetley to allow him into school before the whistle had blown, and repeat the tale to the Headmistress.

By the time the police had been informed not only of Eddy’s tale, but also his proclivities in inventing stories (with several examples), and they decided they had better take a look anyway, it was past mid-morning break. It was even later by the time they had routed out the local bobby who knew which clump of trees beside which ‘old potter’s field’ was being referred to. (Getting Eddy to show them did not get past first base with the school.) By then, of course, every single family who had a child at Fairview Estate Primary, and every single morning golfer at the next-door club, knew exactly what was amiss.

Given the proximity of the alleged crime scene to the school, several of the more nervous, or politically correct, parents demanded the return of their precious offspring to their homes and families. These delicate children proceeded to spend their entire free afternoon doing their best to impede the police by violating the cordon the officers of the law were trying to maintain around the body. Given that, apart from P.C. Johns, the children had the advantage of knowing the ground much better than their adversaries, and had much less interest in keeping themselves clean or tidy; until several car-loads of reinforcements arrived, it was a losing battle. For the children, it was the best day ever.

Miriam went to work at her usual time. But she stopped off on the way. The tale she told to the police covered a lot more ground than the previous night’s activities. It shattered the complacency at the golf club. But it, eventually, allowed Miriam to resume her interrupted education and gave Eddy the chance of a normal life. Miriam insisted she spoke with a female officer. The young detective constable had not anticipated her first case would be so dramatic and far-reaching.

Social services were notified. So was the school. This time, at last, both authorities took action. Eddy was met at school. He was hugged by his – best to say big sister for the moment – and told he would see her again, but he had to go with these kind people for now.

Before that, there had been a planned visit to the farm. Miriam, sent home from work, let them in. Scene of crime (now they know they have an original crime scene) were ready.

‘What’s this?’ her disabled father, acting all innocent, all nice.

‘They’ve come to arrest you, Dad.’

‘Why? What have I done?

One officer started to go through the words of the arrest. A punch, from a suddenly-able-to-stand George Roberts, floored him. A wooden dining chair smashed into the upper body of the second officer. It took five of them to subdue him, putting paid to any idea he should continue receiving disability benefits. As he was dragged away, he was roaring about the man being alive. Dammit, he’d walked out of the house!

The evidence said otherwise. Blood splatter showed he’d been felled (though with what was never determined) in the middle of the lounge floor. He had then been placed in the wheelchair by someone wearing – ‘you did say these were your gloves, sir?’ The body was pushed in the wheelchair half-way down the field, before being tipped out and allowed to rest against the trees. There was an attempt to clean the wheelchair, but forensics can find the smallest amount of mud.

Then he left his own son to find the body! How could he treat a seven-year-old child that way? However, they now know how he’d treated his own daughter, don’t they? DNA tests don’t lie, no matter what birth certificates might say. A home birth indeed! A home, unsupervised birth – it’s amazing Miriam survived. And then to force her into that work at the golf club!

Dad pleaded not guilty. Miriam; petite, slim, abused Miriam, stood in the witness box and wept. Dad’s barrister got told off by the judge. Miriam said, through sobs, she’d done what she’d been told, and she was sorry if she spoilt the crime scene for the police, but Dad said he’d beat her worse than the clients at the golf club if she didn’t do as he said! And him being disabled was a con! She was hysterical by this stage, so the court adjourned for a break.

Dad served two years. The trouble with prison is, it has its own ideas of right and wrong. Murder, in the right circumstances and depending on who the victim is, can get you respect. Using, or abusing, your own daughter, especially when the abuse started when she was underage (she was at school, wasn’t she?): no. No respect whatsoever. And if the screws are a little slow in coming to your aid, that’s just tough, isn’t it? Officially, Dad’s death was due to heart failure.

Things have changed at the (renamed and rebranded) golf club. The member’s bedroom is now kept locked, the key has to be signed for, and the committee informed, every time the room is used. Darren did not even bother to serve out his notice period. Sir Roger, absolutely appalled he missed all the signs, demanded full disclosure to the police (including names), which led to the resignation of every single male member of the old committee – quite a few of whom are now facing divorce proceedings. Sir Roger (Lieutenant-General Sir Roger – retired) has achieved total victory with this last campaign. He is now undisputed chair of the committee, and has insisted the club’s members will take Miriam under their collective wing. Any help she requires – for herself or her son – will, ladies and gentlemen, be given on a pro bono basis. Further, the two of them will, always and at all times, be treated with every courtesy and with utmost respect. It is the least the club can do, under the circumstances. Does anybody wish to speak against …?

Miriam has her counsellors, and her advisers (financial and legal). After her father’s death, the farm had to be sold, but she and Eddy will get the barn conversion. It is not entirely altruistic: the golf club is expanding to become an eighteen-hole course. Miriam also has tutors. She already has her GCSEs, her A-level grades should be good enough for university this autumn. She wants to study criminology.

Specifically, one murder and its associated unasked questions. Like: those missing three hours? What happened? What if she saw, out of her father’s bedroom window – when she went to draw the curtains – the developer leaning against his car, struggling to use his mobile? (Not that she ever worked out if Dad had also disabled the car, or the developer felt too beaten up to drive away – or even too determined to call the police and be there to have Dad arrested for assault, but he just couldn’t get a mobile signal.) What if she realised, even if Dad was convicted of assault, he’d only get a few months, and she and Eddy wouldn’t be free of him – but if it was murder …? What if she had opened the front door, and offered the use of their landline – having assured the developer her father was ‘out of the way,’ but not telling him their phone was disconnected? And, what if the murder weapon had been the frozen lump of meat, the one she’d just got out of the freezer to thaw overnight? And if she had used both hands to raise it high and bring it smashing down on his head? The secret would always be kept from Eddy – she hadn’t used the ‘sharp’ end – the death was due to ‘blunt force trauma.’ The eco-friendly paper, string, and temporary wooden handle all burnt easily.

She and Eddy spent days eating the meat in a stew.